Rousseau: Philosophical Christianity

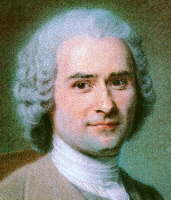

Jean Jacques Rousseau:

Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar, 1782

1782

The Savoyard Vicar and his "Profession of Faith" are introduced into "Emile" not, according to the author, because he wishes to exhibit his principles as those which should be taught, but to give an example of the way in which religious matters should be discussed with the young. Nevertheless, it is universally recognized that these opinions are Rousseau's own, and represent in short form his characteristic attitude toward religious belief. The Vicar himself is believed to combine the traits of two Savoyard priests whom Rosseau knew in his youth. The more important was the Abbe Gaime, whom he had known at Turin; the other, the Abbe Gatier, who had taught him at Annecy.

Introduction

About thirty years ago a young man, who had forsaken his own country and rambled into Italy, found himself reduced to a condition of great poverty and distress. He had been bred a Calvinist; but in consequence of his misconduct and of being unhappily a fugitive in a foreign country, without money or friends, he was induced to change his religion for the sake of subsistence. To this end he procured admittance into a hospice for catechumens, that is to say, a house established for the reception of proselytes. The instructions he here received concerning some controversial points excited doubts he had not before entertained, and first caused him to realize the evil of the step he had taken. He was taught strange dogmas, and was eye-witness to stranger manners; and to these he saw himself a destined victim. He now sought to make his escape, but was prevented and more closely confined. If he complained, he was punished for complaining; and, lying at the mercy of his tyrannical oppressors, found himself treated as criminal because he could not without reluctance submit to be so.

Let those who are sensible how much the first acts of violence and injustice irritate young and inexperienced minds, judge of the situation of this unfortunate youth. Swollen with indignation, the tears of rage burst from his eyes. He implored the assistance of heaven and earth in vain; he appealed to the whole world, but no one attended to his plea. His complaints could reach the ears only of a number of servile domestics, - slaves to the wretch by whom he was thus treated, or accomplices in the same crime, - who ridiculed his non-conformity and endeavored to secure his imitation. He would doubtless have been entirely ruined had it not been for the good offices of an honest ecclesiastic, who came to the hospital on some business, and with whom he found an opportunity for a private conference. The good priest was himself poor, and stood in need of every one's assistance; the oppressed proselyte, however, stood yet in greater need of him. The former did not hesitate, therefore, to favor his escape, even at the risk of making a powerful enemy.

Having escaped from vice only to return to indigence, this young adventurer struggled against his destiny without success. For a moment, indeed, he thought himself above it, and at the first prospect of good fortune, his former distresses and his protector were forgotten together. He was soon punished, however, for his ingratitude, as his groundless hopes soon vanished. His youth stood in vain on his side; his romantic notions proving destructive to all his designs. Having neither capacity nor address to surmount the difficulties that fell in his way, and being a stranger to the virtues of moderation and the arts of knavery, he attempted so many things that he could bring none to perfection, Hence, having fallen into his former distress, and being not only in want of clothes and lodging, but even in danger of perishing with hunger, he recollected his former benefactor.

To him he returned, and was well received. The sight of the unhappy youth brought to the poor vicar's mind the remembrance of a good action; - a remembrance always grateful to an honest mind. This good priest was naturally humane and compassionate. His own misfortunes had taught him to feel for those of others, nor had prosperity hardened his heart. In a word, the maxims of true wisdom and conscious virtue had confirmed the kindness of his natural disposition. He cordially embraced the young wanderer, provided for him a lodging, and shared with him the slender means of his own subsistence. Nor was this all: he went still farther, freely giving him both instruction and consolation, and also endeavoring to teach him the difficult art of supporting adversity with patience. Could you believe, ye sons of prejudice! that a priest, and a priest in Italy too, could be capable of this?

This honest ecclesiastic was a poor Savoyard, who having in his younger days incurred the displeasure of his bishop, was obliged to pass the mountains in order to seek that provision which was denied him in his own country. He was neither deficient in literature nor understanding; his talents, therefore, joined with an engaging appearance, soon procured him a patron, who recommended him as tutor to a young man of quality. He preferred poverty, however, to dependence; and, being a stranger to the manners and behavior of the great, he remained but a short time in that situation. In quitting this service, however, he fortunately did not lose the esteem of his friend; and, as he behaved with great prudence and was universally beloved, he flattered himself that he shoud in time regain the good opinion of his bishop also, and be rewarded with some little benefice in the mountains, where he hoped to spend in tranquillity and peace the remainder of his days. This was the height of his ambition.

Interested by a natural affinity in favor of the young fugitive, he examined very carefully into his character and disposition. In this examination, he saw that his misfortunes had already debased his heart; - that the shame and contempt to which he had been exposed had depressed his ambition, and that his disappointed pride, converted into indignation, had deduced, from the injustice and cruelty of mankind, the depravity of human nature and the emptiness of virtue. He had observed religion made use of as a mask to self-interest, and its worship as a cloak to hypocrisy. He had seen the terms heaven and hell prostituted in the subtility of vain disputes; the joys of the one and the pains of the other being annexed to a mere repetition of words. He had observed the sublime and primitive idea of the Divinity disfigured by the fantastical imaginations of men; and, finding that in order to believe in God it was necessary to give up that understanding he hath bestowed on us, he held in the same disdain as well the sacred object of our idle reveries as those idle reveries themselves. Without knowing anything of natural causes, or giving himself any trouble to investigate them, he remained in a condition of the most stupid ignorance, mixed with profound contempt for those who pretended to greater knowledge than his own.

A neglect of all religious duties leads to a neglect of all moral obligations. The heart of this young vagabond had already made a great progress from one toward the other. Not that he was constitutionally vicious; but misfortune and incredulity, having stifled by degrees the propensities of his natural disposition, were hurrying him on to ruin, adding to the manners of a beggar the principles of an atheist.

His ruin, however, though almost inevitable, was not absolutely completed. His education not having been neglected, he was not without knowledge. He had not yet exceeded that happy term of life, wherein the youthful blood serves to stimulate the mind without inflaming the passions, which were as yet unrelaxed and unexcited. A natural modesty and timidity of disposition had hitherto supplied the place of restraint, and prolonged the term of youthful innocence. The odious example of brutal depravity, and of vices without temptation, so far from animating his imagination, had mortified it. Disgust had long supplied the place of virtue in the preservation of his innocence, and to corrupt this required more powerful seductions.

The good priest saw the danger and the remedy. The difficulties that appeared in the application did not deter him from the attempt. He took a pleasure in the design, and resolved to complete it by restoring to virtue the victim he had snatched from infamy.

To this end he set out resolutely in the execution of his project. The merit of the motive increased his hopes, and inspired means worthy of his zeal. Whatever might be the success, he was sure that he should not throw away his labor: - we are always sure so far to succeed in well doing.

He began with striving to gain the confidence of the proselyte by conferring on him his favors disinterestedly, - by never importuning him with exhortations, and by descending always to a level with his ideas and manner of thinking. It must have been all affecting sight to see a grave divine become the comrade of a young libertine - to see virtue affect the air of licentiousness - in order to triumph the more certainly over it. Whenever the heedless youth made him the confidant of his follies, and unbosomed himself freely to his benefactor, the good priest listened attentively to his stories; and, without approving the evil, interested himself in the consequences. No ill-timed censure ever indiscreetly checked the pupil's communicative temper. The pleasure with which he thought himself heard increased that which he took in telling all his secrets. Thus he was induced to make a free and general confession without thinking he was confessing anything.

Having thus made himself master of the youth's sentiments and character, the priest was enabled to see clearly that, without being ignorant for his years, he had forgotten almost everything of importance for him to know, and that the state of meanness into which he had fallen had almost stifled in him the sense of good and evil. There is a degree of low stupidity which deprives the soul as it were of life; the voice of conscience is also but little heard by those who think of nothing but the means of subsistence. To rescue this unfortunate youth from the moral death that so nearly threatened him, he began, therefore, by awakening his self-love and exciting in him a due regard for himself. He represented to his imagination a more happy success, from the future employment of his talents; he inspired him with a generous ardor by a recital of the commendable actions of others, and by raising his admiration of those who performed them. In order to detach him insensibly from an idle and vagabond life, he employed him in copying books; and under pretence of having occasion for such extracts, cherished in him the noble sentiment of gratitude for his benefactor. By this method he also instructed him indirectly by the books he employed him to copy; and induced him to entertain so good an opinion of himself as to think he was not absolutely good for nothing, and to hold himself not quite so despicable in his own esteem as he had formerly done.

A trifling circumstance may serve to show the art which this benevolent instructor made use of to insensibly elevate the heart of his disciple, without appearing to think of giving him instruction. This good ecclesiastic was so well known and esteemed for his probity and discernment, that many persons chose rather to entrust him with the distribution of their alms than the richer clergy of the cities. Now it happened that receiving one day a sum of money in charge for the poor, the young man had the meanness to desire some of it, under that title, for himself. "No," replied his kind benefactor, "you and I are brethren; you belong to me, and I should not apply the charity entrusted with me to my own use." He then gave him the desired sum from his private funds. Lessons of this kind are hardly ever thrown away on young people, whose hearts are not entirely corrupted.

But I will continue to speak no longer in the third person, which is indeed a superfluous caution; as you, my dear countrymen, are very sensible that the unhappy fugitive I have been speaking of is myself. I believe that I am now so far removed from the irregularities of my youth as to dare to avow them, and think that the hand which extricated me from them is too well deserving of my gratitude for me not to do it honour even at the expense of a little shame.

The most striking circumstance of all was to observe in the retired life of my worthy master virtue without hypocrisy and humanity without weakness. His conversation was always honest and simple, and his conduct ever conformable to his discourse. I never found him troubling himself whether the persons he assisted went constantly to vespers-whether they went frequently to confession - or fasted on certain days of the week. Nor did I ever know him to impose on them any of those conditions without which a man might perish from want, and have no hope of relief from the devout.

Encouraged by these observations, so far was I from affecting in his presence the forward zeal of a new proselyte, that I took no pains to conceal my thoughts, nor did I ever remark his being scandalized at this freedom. Hence, I have sometimes said to myself, he certainly overlooks my indifference for the new mode of worship I have embraced, in consideration of the disregard which he sees I have for that in which I was educated; as he finds my indifference is not partial to either. But what could I think when I heard him sometimes approve dogmas contrary to those of the Romish church, and appear to hold its ceremonies in little esteem? I should have been apt to consider him a protestant in disguise, had I seen him less observant of those very ceremonies which he seemed to think of so little account; but knowing that he acquitted himself as punctually of his duties as a priest in private as in public, I knew not how to judge of these seeming contradictions. If we except the failing which first brought him into disgrace with his superior, and of which he was not altogether corrected, his life was exemplary, his manners irreproachable, and his conversation prudent and sensible. As I lived with him in the greatest intimacy, I learned every day to respect him more and more; and as he had entirely won my heart by so many acts of kindness, I waited with an impatient curiosity to know the principles on which a life and conduct so singular and uniform could be founded.

It was some time, however, before this curiosity was satisfied, as he endeavoured to cultivate those seeds of reason and goodness which he had endeavoured to instill, before he would disclose himself to his disciple. The greatest difficulty he met with was to eradicate from my heart a proud misanthropy, a certain rancorous hatred which I bore to the wealthy and fortunate, as if they were made so at my expense, and had usurped apparent happiness from what should have been my own. The idle vanity of youth, which is opposed to all constraint and humiliation, encouraged but too much my propensity to indulge this splenetic humor; whilst that self-love, which my mentor strove so earnestly to cherish, by increasing my pride, rendered mankind, in my opinion, still more detestable, and only added to my hatred of them the most egregious contempt.

Without directly attacking this pride, he yet strove to prevent it from degenerating into barbarity, and without diminishing my self-esteem, made me less disdainful of my neighbors. In withdrawing the gaudy veil of external appearances, and presenting to my view the real evils it concealed, he taught me to lament the failings of my fellow creatures, to sympathize with their miseries, and to pity instead of envying them. Moved to compassion for human frailties from a deep sense of his own, he saw mankind everywhere the victims of either their own vices or of the vices of others, - he saw the poor groan beneath the yoke of the rich, and the rich beneath the tyranny of their own idle habits and prejudices.

"Believe me," said he, "our mistaken notions of things are so far from hiding our misfortunes from our view, that they augment those evils by rendering trifles of importance, and making us sensible of a thousand wants which we should never have known but for our prejudices. Peace of mind consists in a contempt for everything that may disturb it. The man who gives himself the greatest concern about life is he who enjoys it least; and he who aspires the most earnestly after happiness is always the one who is the most miserable."

"Alas!" cried I, with all the bitterness of discontent, "what a deplorable picture do you present of human life! If we may indulge ourselves in nothing, to what purpose were we born? If we must despise even happiness itself, who is there that can know what it is to be happy?"

"I know," replied the good priest, in a tone and manner that struck me.

"You!" said I, "so little favored by fortune! so poor! exiled! persecuted! can you be happy? And if you are, what have you done to purchase happiness?"

"My dear child," he replied, embracing me, "I will willingly tell you. As you have freely confessed to me, I will do the same to you. I will disclose to you all the sentiments of my heart. You shall see me, if not such as I really am, at least such as I believe myself to be: and when you have heard my whole Profession of Faith-when you know fully the situation of my heart-you will know why I think myself happy; and, if you agree with me, what course you should pursue in order to become so likewise.

"But this profession is not to be made in a moment. It will require some time to disclose to you my thoughts on the situation of mankind and on the real value of human life. We will therefore take a suitable opportunity for a few hours' uninterrupted conversation on this subject."

As I expressed an earnest desire for such an opportunity, an appointment was made for the next morning. We rose at the break of day and prepared for the journey. Leaving the town, he led me to the top of a hill, at the foot of which ran the river Po, watering in its course the fertile vales. That immense chain of mountains, called the Alps, terminated the distant view. The rising sun cast its welcome rays over the gilded plains, and, by projecting the long shadows of the trees, the houses, and adjacent hills, formed the most beautiful scene ever mortal eye beheld. One might have been almost tempted to think that nature had at this moment displayed all this grandeur and beauty as a subject for our conversation. Here it was that, after contemplating for a short time the surrounding objects in silence, my teacher and benefactor confided to me with impressive earnestness the principles and faith which governed his life and conduct.

Part I.

Expect from me neither learned declamations nor profound arguments. I am no great philosopher, and give myself but little trouble in regard to becoming such. Still I perceive sometimes the glimmering of good sense, and have always a regard for the truth. I will not enter into any disputation, or endeavor to refute you; but only lay down my own sentiments in simplicity of heart. Consult your own during this recital: this is all I require of you. If I am mistaken, it is undesignedly, which is sufficient to absolve me of all criminal error; and if I am right, reason, which is common to us both, shall decide. We are equally interested in listening to it, and why should not our views agree?

I was born a poor peasant, destined by my situation to the business of husbandry. It was thought, however, much more advisable for me to learn to get my bread by the profession of a priest, and means were found to give me a proper education. In this, most certainly, neither my parents nor I consulted what was really good, true, or useful for me to know; but only that I should learn what was necessary to my ordination. I learned, therefore, what was required of me to learn, - I said what was required of me to say - and, accordingly, was made a priest. It was not long, however, before I perceived too plainly that, in laying myself under an obligation to be no longer a man, I had engaged for more than I could possibly perform.

Some will tell us that conscience is founded merely on our prejudices, but I know from my own experience that its dictates constantly follow the order of nature, in contradiction to all human laws and institutions. We are in vain forbidden to do this thing or the other-we shall feel but little remorse for doing any thing to which a well-regulated natural instinct excites us, how strongly soever prohibited by reason. Nature, my dear youth, hath hitherto in this respect been silent in you. May you continue long in that happy state wherein her voice is the voice of innocence! Remember that you offend her more by anticipating her instructions than by refusing to hear them. In order to know when to listen to her without a crime, you should begin by learning to check her insinuations.

I had always a due respect for marriage as the first and most sacred institution of nature. Having given up my right to enter into such an engagement, I resolved, therefore, not to profane it: for, notwithstanding my manner of education, as I had always led a simple and uniform life, I had preserved all that clearness of understanding in which my first ideas were cultivated. The maxims of the world had not obscured my primitive notions, and my poverty kept me at a sufficient distance from those temptations that teach us the sophistry of vice.

The virtuous resolution I had formed, was, however, the very cause of my ruin, as my determination not to violate the rights of others, left my faults exposed to detection. To expiate the offence, I was suspended and banished; falling a sacrifice to my scruples rather than to my incontinence. From the reproaches made me on my disgrace, I found that the way to escape punishment for an offence is often by committing a greater.

A few instances of this kind go far with persons capable of reflection. Finding by sorrowful experience that the ideas I had formed of justice, honesty, and other moral obligations were contradicted in practice, I began to give up most of the opinions I had received, until at length the few which I retained being no longer sufficient to support themselves, I called in question the evidence on which they were established. Thus, knowing hardly what to think, I found myself at last reduced to your own situation of mind, with this difference only, that my unbelief being the later fruit of a maturer age, it was a work of greater difficulty to remove it.

I was in that state of doubt and uncertainty in which Descartes requires the mind to be involved, in order to enable it to investigate truth. This disposition of mind, however, is too disquieting to long continue, its duration being owing only to indolence or vice. My heart was not so corrupt as to seek fresh indulgence; and nothing preserves so well the habit of reflection as to be more content with ourselves than with our fortune.

I reflected, therefore, on the unhappy lot of mortals floating always on the ocean of human opinions, without compass or rudder-left to the mercy of their tempestuous passions, with no other guide than an inexperienced pilot, ignorant of his course, as well as from whence he came, and whither he is going. I often said to myself: I love the truth - I seek, yet cannot find it. Let any one show it to me and I will readily embrace it. Why doth it hide its charms from a heart formed to adore them?

I have frequently experienced at times much greater evils; and yet no part of my life was ever so constantly disagreeable to me as that interval of scruples and anxiety. Running perpetually from one doubt and uncertainty to another, all that I could deduce from my long and painful meditations was incertitude, obscurity, and contradiction; as well with regard to my existence as to my duty.

I cannot comprehend how any man can be sincerely a skeptic on principle. Such philosophers either do not exist, or they are certainly the most miserable of men. To be in doubt, about things which it is important for us to know, is a situation too perplexing for the human mind; it cannot long support such incertitude; but will, in spite of itself, determine one way or the other, rather deceiving itself than being content to believe nothing of the matter.

What added further to my perplexity was, that as the authority of the church in which I was educated was decisive, and tolerated not the slightest doubt, in rejecting one point, I thereby rejected in a manner all the others. The impossibility of admitting so many absurd decisions, threw doubt over those more reasonable. In being told I must believe all, I was prevented from believing anything, and I knew not what course to pursue.

In this situation I consulted the philosophers. I turned over their books, and examined their several opinions. I found them vain, dogmatical and dictatorial-even in their pretended skepticism. Ignorant of nothing, yet proving nothing; but ridiculing one another instead; and in this last particular only, in which they were all agreed, they seemed to be in the right. Affecting to triumph whenever they attacked their opponents, they lacked everything to make them capable of a vigorous defence. If you examine their reasons, you will find them calculated only to refute: If you number voices, every one is reduced to his own suffrage. They agree in nothing but in disputing, and to attend to these was certainly not the way to remove my uncertainty.

I conceived that the weakness of the human understanding was the first cause of the prodigious variety I found in their sentiments, and that pride was the second. We have no standard with which to measure this immense machine; we cannot calculate its various relations; we neither know the first cause nor the final effects; we are ignorant even of ourselves; we neither know our own nature nor principle of action; nay, we hardly know whether man be a simple or compound being. Impenetrable mysteries surround us on every side; they extend beyond the region of sense; we imagine ourselves possessed of understanding to penetrate them, and we have only imagination. Every one strikes out a way of his own across this imaginary world; but no one knows whether it will lead him to the point he aims at. We are yet desirous to penetrate, to know, everything. The only thing we know not is to contentedly remain ignorant of what it is impossible for us to know. We had much rather determine at random, and believe the thing which is not, than to confess that none of us is capable of seeing the thing that is. Being ourselves but a small part of that great whole, whose limits surpass our most extensive views, and concerning which its creator leaves us to make our idle conjectures, we are vain enough to decide what that whole is in itself, and what we are in relation to it.

But were the philosophers in a situation to discover the truth, which of them would be interested in so doing? Each knows very well that his system is no better founded that the systems of others; he defends it, nevertheless, because it is his own. There is not one of them, who, really knowing truth from falsehood, would not prefer the latter, if of his own invention, to the former, discovered by any one else. Where is the philosopher who would not readily deceive mankind, to increase his own reputation? Where is he who secretly proposes any other object than that of distinguishing himself from the rest of mankind? Provided he raises himself above the vulgar, and carries away the prize of fame from his competitors, what doth he require more? The most essential point is to think differently from the rest of the world. Among believers he is an atheist, and among atheists he affects to be a believer.

The first fruit I gathered from these meditations was to learn to confine my enquiries to those things in which I was immediately interested, - to remain contended in a profound ignorance of the rest; and not to trouble myself so far as even to doubt about what it did not concern me to know.

I could further see that instead of clearing up any unnecessary doubts, the philosophers only contributed to multiply those which most tormented me, and that they resolved absolutely none. I therefore applied to another guide, and said to myself, let me consult my innate instructor, who will deceive me less than I may be deceived by others; or at least the errors I fall into will be my own, and I shall grow less depraved in the pursuit of my own illusions, than in giving myself up to the deceptions of others.

Taking a retrospect, then, of the several opinions which had successively prevailed with me from my infancy, I found that, although none of them were so evident as to produce immediate conviction, they had nevertheless different degrees of probability, and that my innate sense of truth and falsehood leaned more or less to each. On this first observation, proceeding to compare impartially and without prejudice these different opinions with each other, I found that the first and most common was also the most simple and most rational; and that it wanted nothing more to secure universal suffrage, than the circumstance of having been last proposed. Let us suppose that all our philosophers, ancient and modern, had exhausted all their whimsical systems of power, chance, fate, necessity, atoms, an animated world, sensitive matter, materialism, and of every other kind; and after them let us imagine the celebrated Dr. Clarke enlightening the world by displaying the being of beings - the supreme and sovereign disposer of all things. With what universal admiration, - with what unanimous applause would not the world receive this new system, - so great, so consolatory, so sublime, - so proper to elevate the soul, to lay the foundations of virtue, - and at the same time so striking, so enlightened, so simple, - and, as it appears to me, pregnant with less incomprehensibilities and absurdities than all other systems whatever! I reflected that unanswerable objections might be made to all, because the human understanding is incapable of resolving them, no proof therefore could be brought exclusively of any: but what difference is there in proofs! Ought not that system then, which explains everything, to be preferred, when attended with no greater difficulties than the rest?

The love of truth then comprises all my philosophy; and my method of research being the simple and easy rule of common sense, which dispenses with the vain subtilty of argumentation, I reexamined by this principle all the knowledge of which I was possessed, resolved to admit as evident everything to which I could not in the sincerity of my heart refuse to assent, to admit also as true all that seemed to have a necessary connection with it, and to leave everything else as uncertain, without either rejecting or admitting, being determined not to trouble myself about clearing up any point which did not tend to utility in practice.

But, after all, who am I? What right have I to judge of these things? And what is it that determines my conclusions? If, subject to the impressions I receive, these are formed in direct consequence of those impressions, I trouble myself to no purpose in these investigations. It is necessary, therefore, to examine myself, to know what instruments are made use of in such researches, and how far I may confide in their use.

In the first place, I know that I exist, and have senses whereby I am affected. This is a truth so striking that I am compelled to acquiesce in it. But have I properly a distinct sense of my existence, or do I only know it from my various sensations? This is my first doubt; which, at present, it is impossible for me to resolve: for, being continually affected by sensations, either directly from the objects or from the memory; how can I tell whether my self-consciousness be, or be not, something foreign to those sensations, and independent of them.

My sensations are all internal, as they make me sensible of my own existence; but the cause of them is external and independent, as they affect me without my consent, and do not depend on my will for their production or annihilation. I conceive very clearly, therefore, that the sensation which is internal, and its cause or object which is external, are not one and the same thing.

Thus I know that I not only exist but that other beings exists as well as as myself; to with, the objects of my sensations; and though these objects should be nothing but ideas, it is very certain that these ideas are no part of myself.

Now everything that I perceive out of myself, and which acts upon my senses, I call matter; and those portions of matter which I conceive are united in individual beings, I call bodies. Thus all the disputes between Idealists and Materialists signify nothing to me; their distinctions between the appearance and reality of bodies being chimerical.

Hence I have acquired as certain knowledge of the existence of the universe as of my own. I next reflect on the objects of my sensations; and, finding in myself the faculty of comparing them with each other, I perceive myself endowed with an active power with which I was before unacquainted.

To perceive is only to feel or be sensible of things; to compare them is to judge of their existence. To judge of things and to be sensible of them are very different. Things present themselves to our sensations as single and detached from each other, such as they barely exist in nature; but in our intellectual comparison of them they are removed, transported as it were, from place to place, disposed on and beside each other, to enable us to pronounce concerning their difference and similitude. The characteristic faculty of an intelligent, active being is, in my opinion, that of giving a sense to the world exist. In beings merely sensitive, I have searched in vain to discover the like force of intellect; nor can I conceive it to be in their nature. Such passive beings perceive every object singly or by itself; or if two objects present themselves, they are perceived as united into one. Such beings having no power to place one in competition with, beside, or upon the other, they cannot compare them,or judge of their separate existence.

To see two objects at once, is not to see their relations to each other, nor to judge of their difference; as to see many objects, though distinct from one another, is not to reckon their number. I may possibly have in my mind the ideas of a large stick and a small one, without comparing those ideas together, or judging that one is less than the other; as I may look at my hand without counting my fingers.1 The comparative ideas of greater and less, as well as numerical ideas of one, two, etc., are certainly not sensations, although the understanding produces them only from our sensatione.

It has been pretended that sensitive beings distinguish sensations one from the other, by the actual difference there is between those sensations: this, however, demands an explanation. When such sensations are different, a sensitive begin is supposed to distinguish them by their difference; but when they are alike, they can then only distinguish them because they perceive one without the other; for, otherwise, how can two objects exactly alike be distinguished in a simultaneous sensation? Such objects must necessarily be blended together and taken for one and the same; particularly according to that system of philosophy in which it is pretended that the sensations, representative of extension, are not extended.

When two comparative sensations are perceived, they make both a joint and separate impression; but their relation to each other is not necessarily perceived in consequence of either. If the judgment we form of this relation were indeed a mere sensation, excited by the objects, we should never be deceived in it, for it can never be denied that I truly perceive what I feel.

How, therefore, can I be deceived in the relation between these two sticks, particularly, if they are not parallel? Why do I say, for instance, that the little one is a third part as long as the great one, when it is in reality only a fourth? Why is not the image, which is the sensation, conformable to its model, which is the object? It is because I am active when I judge, the operation which forms the comparison is defective, and my understanding, which judges of relations, mixes its errors with the truth of those sensations which are representative of objects.

[Footnote 1: M. de la Condamine tells of a people who knew how to reckon only as far as three. Yet these people must often have seen their fingers without ever having counted five.]

Add to this the reflection, which I am certain you will think striking after duly weighing it, that if we were merely passive in the use of our senses, there would be no communication between them:

so that it would be impossible for us to know that the body we touched with our hands and the object we saw with our eyes were one and the same. Either we should not be able to perceive external objects at all, or they would appear to exist as five perceptible substances of which we should have no method of ascertaining the identity.

Part II.

Whatever name be given to that power of the mind which assembles and compares my sensations, - call it attention, meditation, reflection, or whatever you please, - certain it is that it exists in me, and not in the objects of those sensations. It is I alone who produce it, although it is displayed only in consequence of the impressions made on me by those objects. Without being so far master over myself as to perceive or not to perceive at pleasure, I am still more or less capable of making an examination into the objects perceived.

I am not, therefore, a mere sensitive and passive, but an active and intelligent being; and, whatever philosophers may pretend, lay claim to the honor of thinking. I know only that truth depends on the existence of things, and not on my understanding which judges of them; and that the less such judgment depends on me, the nearer I am certain of approaching the truth. Hence my rule of confiding more on sentiment than reason is confirmed by reason itself.

Being thus far assured of my own nature and capacity, I begin to consider the objects about me; ragarding myself, with a kind of shuddering, as a creature thrown on the wide world of the universe, and as it were lost in an infinite variety of other beings, without knowing anything of what they are, either among themselves or with regard to me.

Everything that is perceptible to my senses is matter, and I deduce all the essential properties of matter from those sensible qualities, which cause it to be perceptible, and which are inseparable from it. I see it sometimes in motion and at other times at rest. This rest may be said to be only relative; but as we perceive degrees in motion, we can very clearly conceive one of the two extremes which is rest; and this we conceive so distinctly, that we are even induced to take that for absolute rest which is only relative. Now motion cannot be essential to matter, if matter can be conceived at rest. Hence I infer that neither motion nor rest are essential to it; but motion being an action, is clearly the effect of cause, of which rest is only the absence. When nothing acts on matter, it does not move; it is equally indifferent to motion and rest; its natural state, therefore, is to be at rest.

Again, I perceive in bodies two kinds of motion; that is a mechanical or communicated motion, and a spontaneous or voluntary one. In the first case, the moving cause is out of the body moved, and in the last, exists within it. I shall not hence conclude, however, that the motion of a watch, for example, is spontaneous; for if nothing should act upon it but the spring, that spring would not wind itself up again when once down. For the same reason, also, I should as little accede to the spontaneous motion of fluids, nor even to heat itself, the cause of their fluidity.

You will ask me if the motions of animals are spontaneous? I will freely answer, I cannot positively tell, but analogy speaks in the affirmative. You may ask me further, how I know there is such a thing as spontaneous motion? I answer, because I feel it. I will to move my arm, and, accordingly, it moves without the intervention of any other immediate cause. It is in vain to attempt to reason me out of this sentiment; it is more powerful than any rational evidence. You might as well attempt to convince me that I do not exist.

If the actions of men are not spontaneous, and there be no such spontaneous action in what passes on earth, we are only the more embarrassed to conceive what is the first cause of all motion. For my part I am so fully persuaded that the natural state of matter is a state of rest, and that it has in itself no principle of activity, that whenever I see a body in motion, I instantly conclude that it is either an animated body or that its motion is communicated to it. My understanding will by no means acquiesce in the notion that unorganized matter can move of itself, or be productive of any kind of action.

The visible universe, however, is composed of inanimate matter, which appears to have nothing in its composition of organization, or that sensation which is common to the parts of an animated body, as it is certain that we ourselves, being parts thereof, do not perceive our existence in the whole. The universe, also, is in motion; and its movements being all regular, uniform, and subjected to constant laws, nothing appears therein similar to that liberty which is remarkable in the spontaneous motion of men and animals. The world, therefore, is not a huge self-moving animal, but receives its motions from some foreign cause, which we do not perceive: but I am so strongly persuaded within myself of the existence of this cause, that it is impossible for me to observe the apparent diurnal revolution of the sun, without conceiving that some force must urge it forward; or if it is the earth itself that turns, I cannot but conceive that some hand must turn it.

If it be necessary to admit general laws that have no apparent relation to matter, from what fixed point must that enquiry set out? Those laws, being nothing real or substantial, have some prior foundation equally unknown and occult. Experience and observation have taught us the laws of motion; these laws, however, determine effects only without; these laws, however, determine effects only without displaying their causes; and, therefore, are not sufficient to explain the system of the universe. Descartes could form a model of the heavens and earth with dice; but he could not give their motions to those dice, nor bring into play his centrifugal force without the assistance of a rotary motion. Newton discovered the law of attraction; but attraction alone would soon have reduced the universe into one solid mass: to this law, therefore, he found it necessary to add a projectile force, in order to account for the revolution of the heavenly bodies. Could Descartes tell us by what physical law his vortices were put and kept in motion? Could Newton produce the hand that first impelled the planets in the tangent of their respective orbits?

The first causes of motion do not exist in matter; bodies receive from and communicate motion to each other, but they cannot originally produce it. The more I observe the action and reaction of the powers of nature acting on each other, the more I am convinced that they are merely effects; and we must ever recur to some volition as the first cause: for to suppose there is a progression of causes to infinity, is to suppose there is no first cause at all. In a word, every motion that is not produced by some other, must be the effect of spontaneous, voluntary act. Inanimate bodies have no action but motion; and there can be no real action without volition. Such is my first principle. I believe, therefore, that a Will gives motion to the universe, and animates all nature. This is my first article of faith.

In what manner volition is productive of physical and corporeal action I know not, but I experience within myself that it is productive of it. I will to act, and the action immediately follows; I will to move my body, and my body instantly moves; but, that an inanimate body lying at rest, should move itself, or produce motion, is incomprehensible and unprecedented. The Will also is known by its effects and not by its essence. I know it as the cause of motion; but to conceive matter producing motion, would be evidently to conceive an effect without a cause, or rather not to conceive any thing at all.

It is no more possible for me to conceive how the will moves the body, than how the sensations affect the soul. I even know not why one of these mysteries ever appeared more explicable than the other. For my own part, whether at the time I am active or passive, the means of union between the two substances appear to me absolutely incomprehensible. Is it not strange that the philosophers have thrown off this incomprehensibility, merely to confound the two substances together, as if operations so different could be better explained as the effects of one subject than of two.

The principle which I have here laid down, is undoubtedly something obscure; it is however intelligible, and contains nothing repugnant to reason or observation. Can we say as much as the doctrines of materialism? It is very certain that, if motion be essential to matter, it would be inseparable from it; it would be always the same in every portion of it, incommunicable, and incapable of increase or diminution; it would be impossible for us even to conceive matter at rest. Again, when I am told that motion is not indeed essential to matter, but necessary to its existence, I see through the attempt to impose on me by a form of words, which it would be more easy to refute, if more intelligible. For, whether the motion of matter arises from itself, and is therefore essential to it, or whether it is derived from some external cause, it is not further necessary to it than as the moving cause acting thereon: so that we still remain under the first difficulty.